Warning: this article contains film spoilers.

At the age of four, Richard Cope, author of Mintel’s 2023 Global Outlook on Sustainability report, went with his Dad to see the 1977 science fiction horror film Empire of the Ants and it’s been downhill ever since. Here, he explores the messaging in the new wave of eco-thriller films and takes a brief look at the history of sustainability in cinema.

Cinema – and especially genre movies – have always held up a mirror to popular culture. As part of our growing engagement levels, are we seeing the stirrings of a return to the heyday of 1970s eco-thrillers? Can this activate us further?

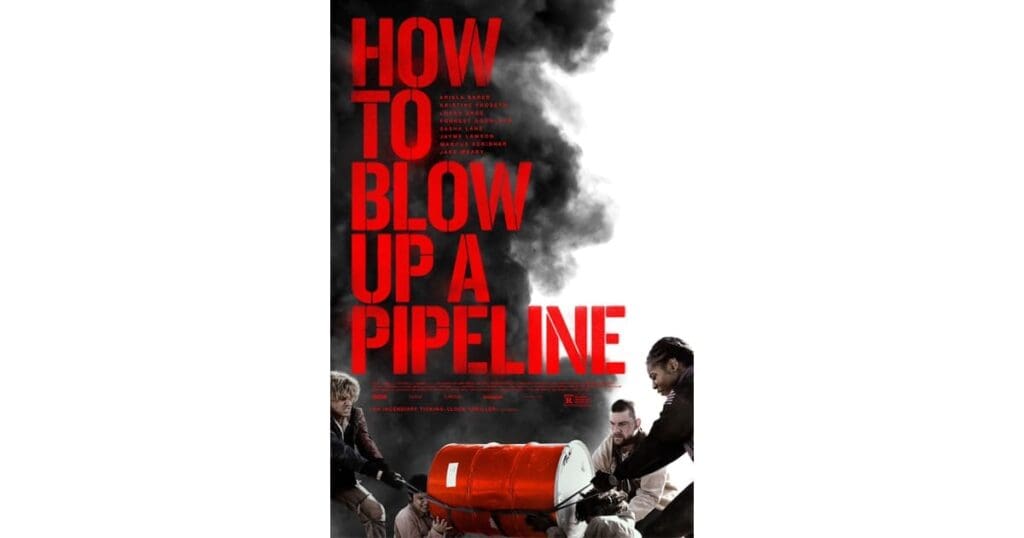

In the film, How to Blow Up a Pipeline (2022, Daniel Goldhaber), twenty-something Californians sickened by pollution from local oil refineries and grieving from losing their mother in an extreme heatwave, hatch a plan with fellow activated environmentalists to destroy a Texan oil pipeline. This mainstream thriller takes on what was originally a manifesto written by Andreas Malm, a professor of human ecology at Lund University in Sweden. It’s intriguing in that it directly addresses how its protagonists are heroes to some, and terrorists to others, whilst portraying activism as the latest installment in the righteous vengeance running through everything from The Searchers (1956, John Ford), to Get Carter (1971, Mike Hodges), Carrie (1976, Brian DePalma) and Old Boy (2003, Park Chan-wook).

Source: Mintel Global Outlook on Sustainability: A Consumer Study, 202338% of Americans say eco-activism is a legitimate form of protest.

At the other end of the scale, in Avatar: The Way of Water (2022, James Cameron) the effects may date instantly and the critics may bray, but the conservationist message is stark, as Jake Sully and Princess Neytiri fight to preserve their idyll of Pandora against the ‘Sky People’.

Elsewhere, in Nope (2022, Jordan Peele), the ecological messages are more concealed, just like ‘Jean Jacket’ the film’s jellyfish-like UFO that hides up in the clouds. Peele has spoken repeatedly about the film’s role as an exploration of our “addiction to spectacle” to the point of exploiting nature, but as its sky-inhabiting villain excretes and rains down torrents of blood, detritus and jewellery from its human victims, it’s impossible to escape pondering ecological analogies around exploitation, emissions and waste.

Prior to these releases, Don’t Look Up (2021, Adam McKay) recorded the clearest commentary on the climate crisis to date, with its often pugilistic Saturday Night Live-style approach proving as divisive as climate change itself. In the film, astronomers, played by Jennifer Lawrence and Leonardo DiCaprio, discover a comet headed on a terminally destructive path towards Earth and then find that no one can be sufficiently diverted from their political greed/celebrity fixations/social media feeds to do anything about it. Most chilling of all, a tech billionaire, played by Mark Rylance, cares only for the comet’s lucrative minerals, safe in the knowledge that his cryogenic escape pod to another world is ready to go.

On the flip side of this characterisation, Edward Norton plays another tech billionaire in Glass Onion: A Knives Out Mystery (2022, Rian Johnson), presented as equally morally bankrupt, but this time recklessly deluded about the prospects of “Klear”, a new hydrogen-based renewable fuel his company is betting the future on without sufficient testing.

Source: Mintel Global Outlook on Sustainability: A Consumer Study, 202355% of global consumers agree ‘If we act now, we still have time to save the planet’.

Don’t Look Up’s importance and genius is in its subversion of previous disaster movies like Deep Impact (1998, Mimi Leder), Armageddon (1998, Michael Bay) and Meteor (1979, Ronald Neame) where giant lumps of space rock headed to earth needed nuking by heroes played by Bruce Willis or Sean Connery. By facing, rather than externalizing, the threat and by excruciatingly embracing the unhappy ending, the film is far more (pardon the pun) impactful than Ronald Emmerich’s star-studded, CGI-realised mini-genre of disaster pics, which thematically progressed from the externalized alien threats of Independence Day (1996) to the human-induced new ice age of The Day After Tomorrow (2004), before retreating into the Mayan-forecasted apocalypse of 2012 (2009) and World War II remakes like Midway (2019).

Whilst meteor movies were evolving, there were other earlier, notable, if less overt meditations on environmental themes, including The Revenant (2015, Alejandro G. Iñárritu) in which Leonardo DiCaprio plays a 19th-century frontiersman whose survival and revenge odyssey doubles as a hymn to the lost wilderness, and First Reformed (2017, Paul Schrader), in which Ethan Hawke plays a repressed pastor who becomes drawn into the lives of an environmentalist couple afraid to bring their unborn child into a world doomed by climate change.

Where might sustainable cinema turn next?

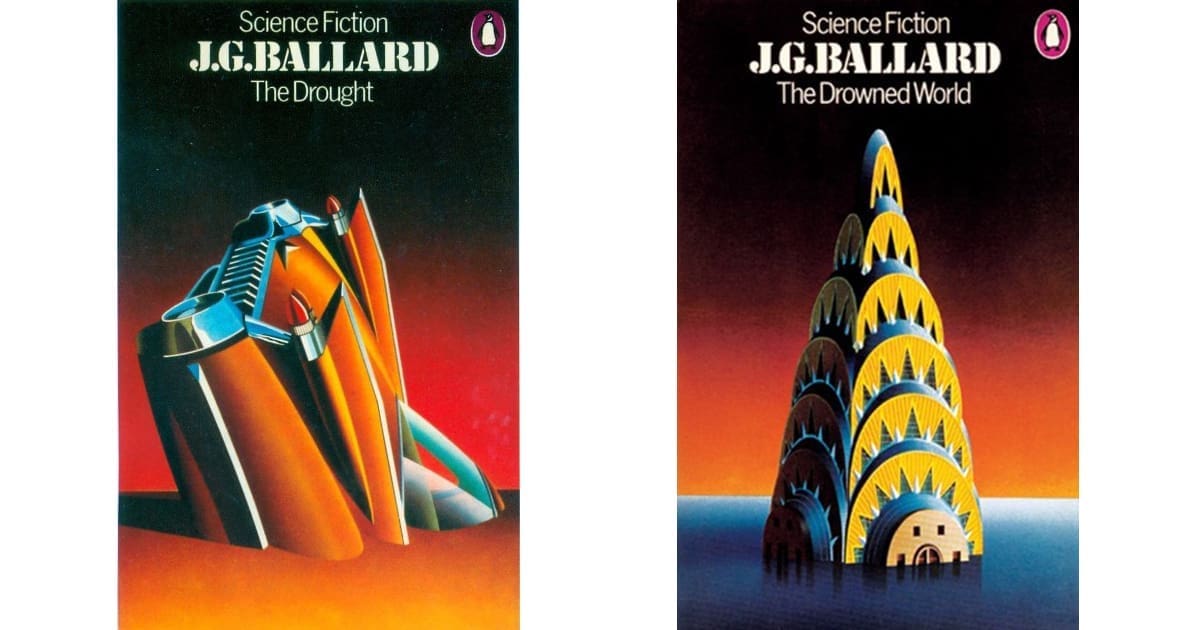

Nope’s otherworldly ancestors were the havoc-wreaking alien invaders of the War of the Worlds (1953, Byron Haskin) and their lower-budgeted 1950s offspring, but the following decade delivered a wealth of untapped potential in the form of JG Ballard’s extraordinarily prescient (and unfilmed) novels The Drowned World (1962) and The Burning World (1964) which respectively explore a world of rising sea levels and tropical climates where people scurry to the poles and another where industrial pollution causes a global drought that drives people desperately to the coasts. Ballard’s apocalyptic worldview and survival instincts were formed by his boyhood experiences in a World War II Shanghai internment camp and are ripe for new interpretations.

Source: Mintel Global Outlook on Sustainability: A Consumer Study, 2023‘Water shortages’ is the number one concern for consumers in Mexico (26%), Spain (25%), and France (20%) and is tied with ‘climate change’ as the top concern in Brazil (16%) and Italy (20%).

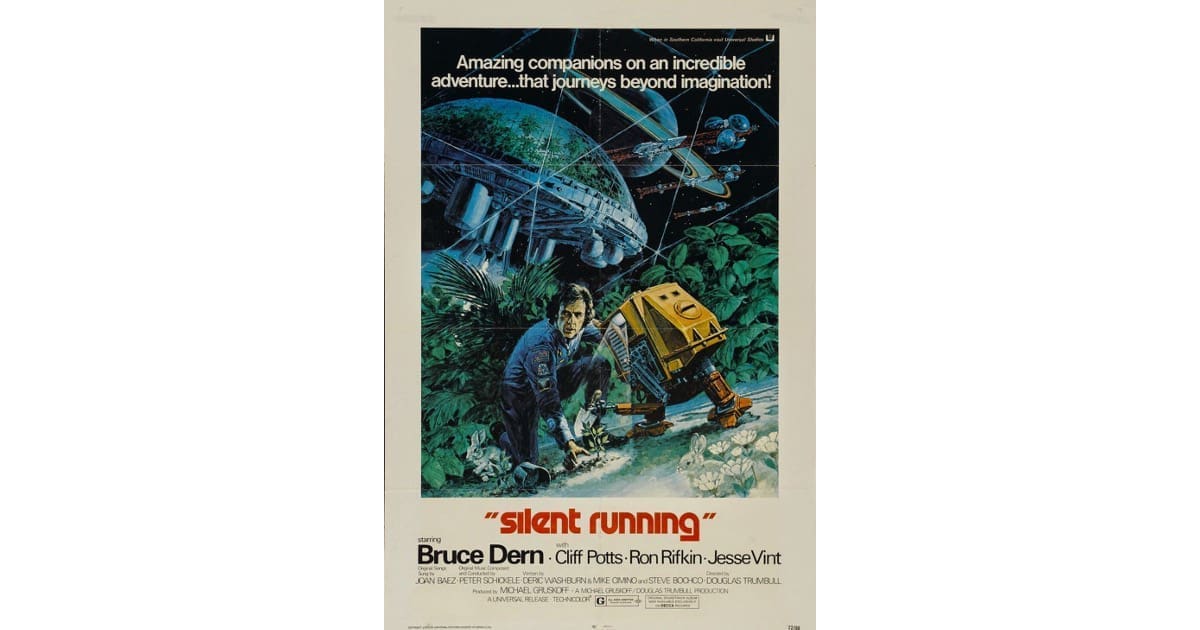

In the 1970s, dystopian Hollywood brought us Soylent Green (1973, Richard Fleischer) in which a NYC Detective, played by Charlton Heston, discovers that polluted, overpopulated planet Earth is resorting to a titular foodstuff made from people. Silent Running (1972, Douglas Trumbull), meanwhile, posited a future where a polluted earth can no longer support its forests so they are taken off-world in giant domes on the spaceship Valley Forge, where they are cared for by a botanist, played by Bruce Dern, and his team of cute robot gardeners. When orders come through to detonate the domes and return the ship to commercial use, Dern fights his fellow crew members to the death and, in an extraordinarily moving climax, sacrifices himself whilst sending the remaining dome into deep space with the last surviving robot.

Hollywood likes a low-budget remake or revival and we may well see it harking back to the golden age of its 1970s “Revenge of Nature” cycle. Coming during the post-hippie environmental awakening, the politics were painfully clear: man messes with the natural order, nature righteously bites back and the body count rises.

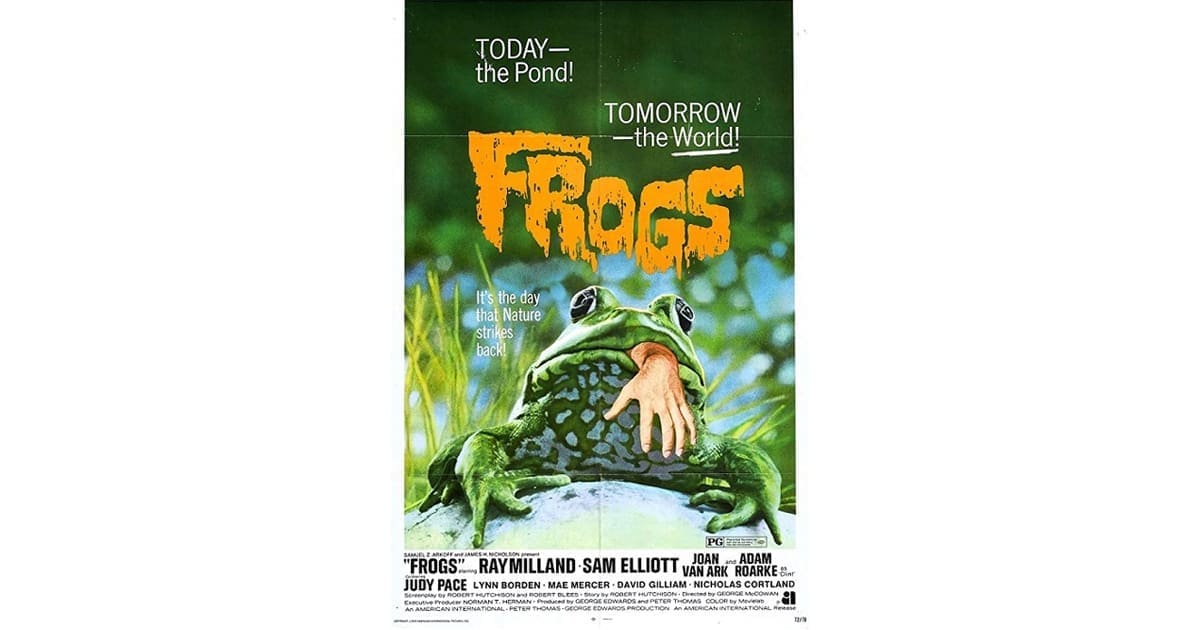

In Frogs (1972, George McCowan) – with the tagline “TODAY, the pond! TOMORROW, the world!” – Ray Milland’s character deals with Florida houseguests that poison and pick off the local reptiles, amphibians, and insects to their great cost. The legendary Night of the Lepus (1972, William F. Claxton) features Arizonians threatened by genetically-meddled, man-eating bunnies and the immortal line “Attention! Attention! Ladies and gentlemen, attention! There is a herd of killer rabbits headed this way and we desperately need your help!”

Bert I Gordon’s Food of the Gods (1976) and Empire of the Ants (1977) leverage (or is that crowbar?) HG Wells’ stories about food growth agents, radioactive waste and the ensuing problems posed by giant killer chickens, wasps, rats and ants. In Day of the Animals (1977, William Girdler) it’s ozone depletion that sends California’s high-altitude beast doolally; whilst in the witty, acerbic Piranha (1978, Joe Dante) it’s mutants created by the military to “destroy the river systems of the North Vietnamese” that are eating their way through the guests at a Texan river resort.

In Orca (1977, Michael Anderson) – a sensitively intentioned if occasionally stupid ‘thinking man’s Jaws’ – a fisherman, played by Richard Harris, finds himself at the business end of a vengeful, grieving killer whale after he kills its mate and calf. In Prophecy (1979, John Frankenheimer), it’s mercury poisoning from a Maine paper mill that’s deforming the local babies and growing the grizzley bears 20-feet high. Maybe the plastic packaging lobby will bankroll a remake.

Source: Mintel Global Outlook on Sustainability: A Consumer Study, 202336% of consumers think companies are ‘most responsible’ for stopping pollution entering rivers and seas.

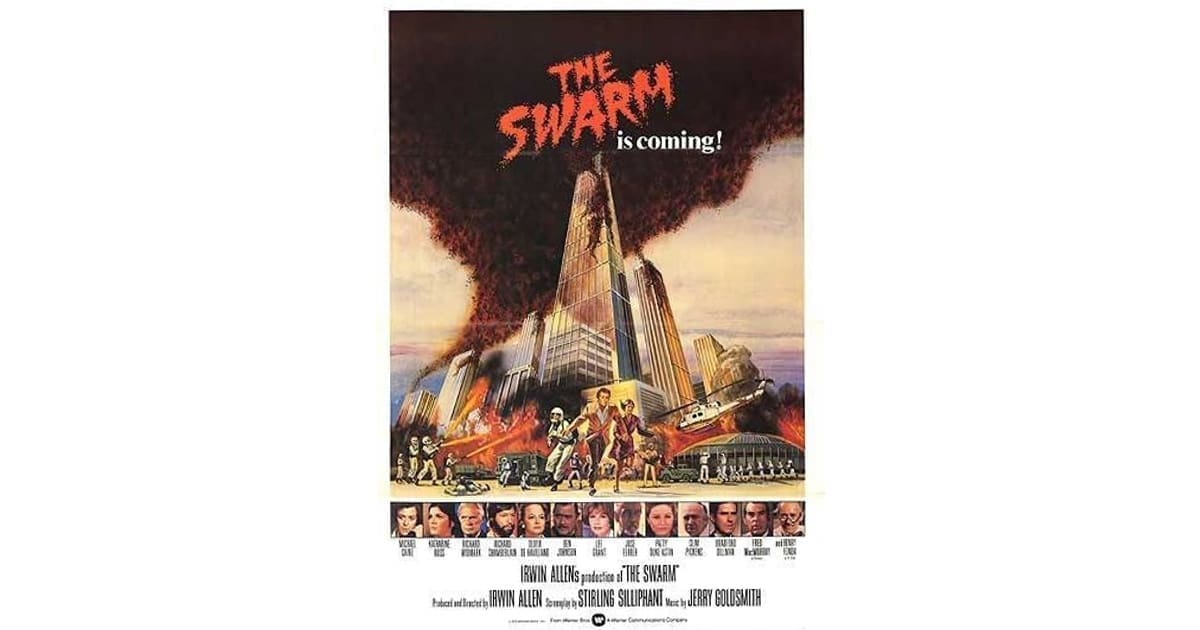

The cycle really climaxed, and bottomed out, with The Swarm (1978, Irwin Allen) in which African killer bees migrate northwards to take out America’s picnicking families, military bases and nuclear installations. These movies trade on the gradual decimation of their starry casts, but the real joy of this film is the entomologist’s, played by Michael Caine, masterclass in delivering shouty sustainability lectures on the need for selective species elimination and the conservation of America’s native pollinators. Even tasty trash like this has the ability to provoke, with Caine’s final line: “If we use our time wisely, the world just might survive.”

Source: Mintel Global Outlook on Sustainability: A Consumer Study, 2023The UN reports that, whilst 75% of fruit and vegetable crops are pollinated by bees, some 35% of bee colonies are disappearing every year.

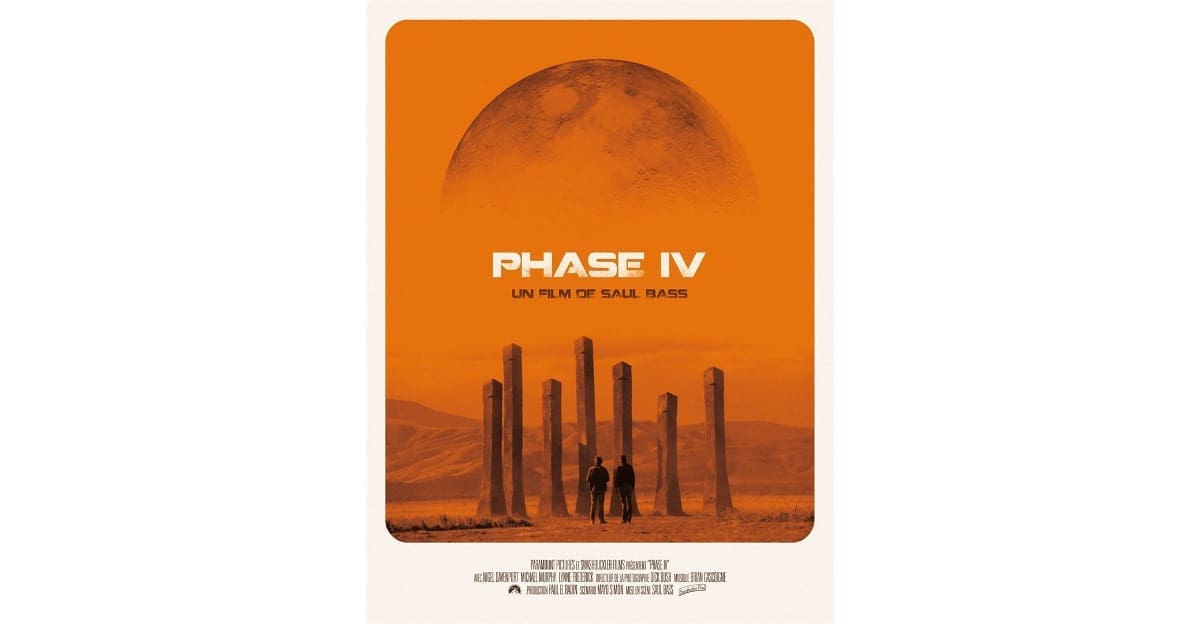

The outlier in this bunch is way beyond anything we’ve seen since and is the kind of film that would seem wild even in our modern environment of climate crisis and cinematic boundary-pushing. In the staggering, trippy, yet coldly-scientific Phase IV (1974, Saul Bass), intelligent ants communicate with humanity, then overcome and corral us before changing the course of our entire evolutionary history, seemingly melding us with fellow fish and amphibians into something entirely new.

A final thought on the topic

We’re running out of time to keep laughing darkly at the well-intentioned warnings of 70s’ genre flicks. What is ‘low’ and ‘high’ art is for the individual to decide, but quality does not dictate levels of influence. Sustainability is rising to the top of personal, political and cinematic agendas and it will be fascinating to see how it is projected going forward.